- Home

- Jack Gerson

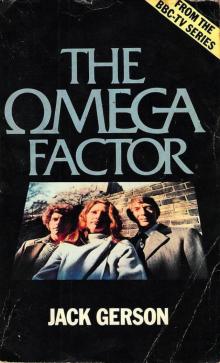

The Omega Factor

The Omega Factor Read online

The Omega Factor

Jack Gerson

First published in the UK in 1979

This ePub edition is version 1.0, released July 2013

For G. and G. without whom...

Prologue

ONE

Plaster flaked from the ceiling.

Fragments fell slowly, twisting and turning, luminous motes floating in the ray of moonlight that came through the side of the curtain.

The boy lay on the bed, eyes open, pupils dilated, staring up at the crack in the ceiling. He knew, if he lengthened the crack, more plaster would flake off and fall. More flakes, like parachutists, floating down inside the ray of light. Easy, if he concentrated hard enough.

He shut his eyes, screwing the lids together tightly. Yet, no matter how tightly he shut his eyes, he was still able to see through his closed eyelids the crack in the corner of the ceiling.

He forced himself to concentrate harder. His face wrinkled in the dim light, the intensity of his thoughts tightening the muscles of the jaw and cheek.

There was an almost imperceptible sound, a small breaking noise. He opened his eyes. The crack had doubled its length. It was now about three feet long, snaking out from the corner. Plaster fell thickly through the moonlight onto the carpet.

After a minute it stopped falling. The boy smiled to himself. Easy. You want something to happen so you concentrate and it happens.

A book fell out of the bookcase in the corner of the bedroom. It seemed to ease itself from between two other books and fall on its spine. The pages opened and the book slid down flat. A ripple like a breeze ran across the open page and then the pages rose and turned themselves over, one after the other, faster and faster. There was no breeze in the room. Only an icy coldness that seemed to descend on the bed, permeate the blankets and cause the boy to shiver.

His smile had gone, replaced by a frown. It had happened before. You made something happen and quite often it did and that was all. But at other times other things happened too. Stupid, pointless things. Things he didn't want. Things he couldn't stop. As if his concentration released other energies.

When it had first happened he had been amused, fascinated to lie and watch objects move without cause, twist and turn of their own volition.

He looked at the table beside his bed. The small glass globe containing the winter scene, a cottage, a tree and a blue patch of pond, the kind of globe you shook to disturb minute particles and create a snow scene, lay immobile on the polished surface of the table. But inside the globe the snow particles were falling and rising, covering the tiny cottage for a moment, then, as if shaken, swirling wildly against the glass.

The boy watched, unwilling to take his eyes away. Other sounds intruded. More books fell from the bookcase. Still he kept his eyes deliberately on the globe. If he could keep his eyes away from what was happening in the room, from what was about to happen in the room, perhaps it would die down quicker.

A chair standing against the wall fell over. A drawer, the top drawer of the massive old dresser opposite the bookcase, opened with a loud creaking sound. This was followed by a rustling as if a hand was running through the contents of the drawer.

Strangely the boy found he had no fear. Even on the first occasion it had happened he had found himself unafraid. Curious at first certainly. But never fearful. Now lying in bed aware of the effect of energies he could not understand he felt only a kind of exhilaration, mixed with an awkward embarrassment.

He knew that what was happening didn't happen to other people. He knew it shouldn't happen. But it did happen to him and, since his eleventh birthday, increasingly more often.

Beneath him the bed started to move. Slowly at first it shuddered and then started to rise and fall. Gradually the tempo increased, the bed rose faster and faster, up and down, thudding into the carpet, resounding on the wooden floor.

The boy was waiting now, head deep in the coolness of the pillow, waiting for the door of the bedroom to open and his parents to rush in. The sound of the bed would echo through the small house and in moments they would throw the door open as they had done on previous occasions, shocked, frightened, helpless against phenomena they could not comprehend.

The bed would continue to rise and fall, drawers open and shut, books fall from the bookcase. This would go on for some moments after the arrival of his mother and father until, as if the energy in the room had dissipated itself in final demonstration, it would die away.

The door was thrown open. The boy looked up at his father and, almost apologetically, tried to smile. Somewhere in the house his two-year-old brother started to cry. Shortly it would be over for another night.

To the average middle-class family, if such a classification exists, a first encounter with the irrational is easily dismissed as some quirk of nature, an accident that might be explained once all the facts are mustered in a correct sequence.

But a continuation of such occurrences produces at first irritation and then anger. When it is related to a child then the child must be to blame. However, when manifestly the child cannot be blamed, and the occurrences continue, fear sets in. And the first reaction to fear is to call in an expert, someone with specialised knowledge. It does not matter that that knowledge may not be in any way directly related to the occurrences.

The boy's parents called in the family doctor.

The family doctor assured them that apart from an occasional rise in temperature, the boy was in perfect health. Faced with the results of the latest incident and the spectacle of a room in wild disarray and a ceiling which was shedding plaster the suspicion that the boy was himself physically causing the chaos could not be avoided by a rather unimaginative medical practitioner. He suggested that he bring in psychiatric help.

The psychiatrist was a man of distinction in his profession. Indeed he was reckoned to be in line for the Chair of Psychiatric Medicine at the nearby University of Glasgow.

The psychiatrist had his first meeting with the boy alone in the sitting room. The boy sat nervously on the edge of a large armchair facing the psychiatrist who sprawled affably on a sofa. They faced each other for a moment in a silence broken only by the ticking of the old-fashioned ormolu clock on the wall.

'I can't help it,' the boy said, breaking the silence.

'Help what?' the psychiatrist asked, assuming what he thought was a look of avuncular benevolence.

'What happens. I only want to make one thing happen. I can do that but other things happen as well.'

'What do you mean, you want to make one thing happen?'

The boy wriggled uneasily. 'Just that. I want to make the plaster fall from the ceiling so I close my eyes and it does. But then the other things happen. The bed rising, the drawers opening. Nothing to do with me. Honest.'

'You mean you can make things happen?'

'Yes.'

'And how do you do that?'

'Just shut my eyes and make it happen. Because I want it,' the boy grinned. It was a likeable grin. A good-looking boy, thought the psychiatrist. Good-looking but clever. Devious.

'You say you can make objects move when you want to? Without touching them?'

'Sometimes.'

The devious answer. Sometimes. Not always. The boy's way out of trouble.

'Why only sometimes?' the psychiatrist inquired assuming a casual air.

'Because it doesn't always happen. But when it does all the other things happen too. And they've got nothing to do with me.'

The psychiatrist looked around. 'Can you do it now? Can you make that ashtray fall off the table?'

The table was a small casual table, one of a nest of tables. The ashtray was of heavy glass and sat solidly in the middle.

'Maybe I could,' the boy replied, star

ing at the ashtray.

Another moment of silence. Nothing happened. The ashtray remained in the centre of the table.

The psychiatrist broke the silence this time. 'Have you ever heard of the word : poltergeist?'

'No. What's that?'

'A kind of ghost. I don't believe they exist except in the minds of credulous people.'

'What's credulous?'

'People who believe in ghosts, who believe in things that don't exist. A poltergeist is supposed to be a mischievous spirit.'

The boy was still staring at the ashtray.

'I don't believe in ghosts either,' he said.

The psychiatrist thought either he's being very clever simply agreeing with his elders, or he's being honest. But if he was being honest then he could be made to admit that he had caused the chaos in his room.

The ashtray fell off the table.

It seemed to fall slowly as if floating to the carpet. Yet it landed with a heavy thud.

The psychiatrist blinked. That shouldn't have happened. The boy couldn't have rigged it in some way to fall. The boy was staring at him now, his face bland.

'Did you do that?' the psychiatrist asked, his voice trembling.

'I... I think so.'

Not possible, the psychiatrist thought. Games being played. Perhaps the parents were involved. No other explanation. Unless one accepts the theory of telekinesis. The production of motion at a distance beyond the range of the senses, that was the dictionary definition of telekinesis. The psychiatrist did not believe in telekinesis.

He stared again at his young patient. The boy seemed calm, relaxed, waiting for the next question. Devious again? For his age he was a very good actor. Or it was genuine. He rejected the last thought.

Something caused him to lean forward, a look in the boy's face he could not instantly define. Then he saw it. An unnatural dilation of the pupil of the eye.

A sudden pain slashed across the psychiatrist's forehead. He jumped back, startled. The stem of a plastic flower fell onto the sofa. He stared at it for a moment then looked around. A vase of plastic flowers stood on another occasional table by the window. The flowers rustled and shook in a glass bowl.

'That wasn't me!' the boy exclaimed vehemently.

The psychiatrist felt his forehead. Perhaps a slight abrasion, nothing more.

'It doesn't usually happen in the sitting room,' the boy went on.

The psychiatrist stood up and picking up the ashtray, examined it. The glass was smooth, unmarked; no sign of threads or any indication of mechanical force which might have propelled it to the floor.

The plastic flowers stopped rustling.

'I don't like plastic flowers,' the boy said. 'I told my mother I don't like them. You should have real flowers or none at all.'

'What happens next?' the psychiatrist asked, trying to simulate a serenity he did not feel.

The boy sat back in the armchair and sighed. I think it's over now.'

'How do you know?'

'I can feel it. Like everything's relaxed. Nothing else is going to happen.'

The psychiatrist decided it was time to go. He wanted to think about what had happened. After all the parents had been genuinely worried. They couldn't be involved with the boy in some kind of hoax. And he had seen two incidents for himself. They had to be thought on, considered as possibly the result of some unique quality within the boy or, alternatively, some clever conjuring trick. Logically he favoured the latter. There was something else too. He was afraid.

And yet the boy was only eleven-years-old. And there was no trace of amusement in his attitude, no indication that he had in some way scored over the adult world. Could he have come across something genuinely unique, or at least one of those rare cases when a child possessed some paranormal ability outside even the child's control?

Some minutes later in the narrow hall of the house he explained to the mother that he would see the boy again in a few days and continue his treatment. He thought to himself as he said it, what treatment? He had asked a few questions, and the boy had demonstrated an ability for which he had no explanation.

The boy was standing a few feet behind his mother. As the psychiatrist opened the front door the boy stepped forward.

'Goodbye,' he said politely but with a sad frown on his face.

'I'll see you next week,' the psychiatrist replied. 'We'll carry on then.'

The boy shook his head. 'No. I'm sorry but we won't.'

The psychiatrist bent forward and smiled at the boy. 'You don't want me to come back?'

'I don't mind. It's just that... that you won't come back.'

The psychiatrist stared at the boy for a moment, and then giving him an uncertain smile, nodded to his mother and stepped outside the door. He walked briskly down the path to the gate, still smiling. The strangeness of his visit had slightly unnerved him and the smile was his defence against his own uncertainty.

The mother watched the car drive away before she shut the front door and turned to the boy.

'Why did you say that? Why did you say he won't come back?'

The boy shrugged. 'I know he won't.'

'How can you know he won't?'

'Because there will be something... and he won't be able to come back.'

The local press in the form of an over-enthusiastic young reporter with an ear to all the town gossip printed a small story on an inner page some weeks later. Without naming the boy or the family the story told of unusual events in a small house on the west side of the town. It mentioned poltergeist phenomena in one paragraph and in the next asked if a modern home could contain a ghost. Any attempts to follow up the story were met with a resounding silence.

The parents and their friends closed ranks. Nothing more was said to outsiders with one exception. The matter was discussed with a priest. Although the family were not Catholics a cousin who was, introduced them to a Jesuit father who lived in the town.

The Jesuit visited the boy one evening in late summer. Nothing happened. For three nights the Jesuit visited the boy and nothing happened. On the fourth night the Jesuit was unable to come. The next morning the boy's room was in a state of disarray.

Despite his deep faith the Jesuit was a practical man. He suggested a holiday for the boy and though it was only early spring the family took the two boys to Spain for two weeks. The holiday passed without incident and after they returned nothing more happened for some months.

However, with the onset of winter, it started again with increasing intensity. Over a period of weeks in late October the boy's room was reduced to a shambles. Furniture was not only moved but smashed. Drawers were opened, upturned and thrown - across the room. Multiple cracks appeared on the ceiling, doors in the house opened and shut without cause. It was as if a protest were being made against the harshness of the season.

Surprisingly this phenomenon had no physical effect on the boy. He seemed healthy and unworried by what was happening. He rarely talked about it and when he did it was with an air of puzzlement. It was as if he was a spectator looking at things over which he had no control.

The Jesuit returned. He faced the family in the sitting-room, the mother, the father and the Catholic cousin. The boy was at school and his younger brother was being looked after by relatives, because the disturbances had made it impossible for him to sleep at night.

The Catholic cousin was the first to bring up the question of exorcism. It was not well received by the priest. His practical outlook caused him to reject the idea strongly. It was medieval, more than that, in his view, positively primitive. Yet, he believed in evil as a strong force in the world but to equate evil with some kind of spiritual manifestation was, he felt, heresy. He agreed that many prelates in the Church would not agree with this viewpoint; in all conscience he himself could not allow of any other. Had they, as a family, considered psychiatric help?

He was aware, as he asked this question, of a hiatus, a pause in the discussion. The parents looked at each other and looked

away. The father muttered quickly that they had tried this without success. The meeting ended without resolution other than that the priest would talk to the boy again.

He did so the next evening with the boy sitting up in bed. He talked of the prevalence of evil forces in the world and how such forces often attached themselves to children, causing wilfulness, disregard for parental authority and varying degrees of mischief. The boy seemed to understand and agree that such things did occur. But it was obvious . that he did not relate them to himself.

Their conversation ended when the Jesuit was cut above the eye by a small ornament, a china cat, which flew across the room and struck him.

In the normal course of his career the Jesuit was transferred just a week later to another town in another country. He accepted the transfer with relief. Somehow he felt he was out of his depth and any further contact with the boy and his family would introduce into his life questions he was loath to pursue. Later, in that other country, he suffered from what he described to himself as a spiritual crisis. He acknowledged even later that this was caused by a conscience disturbed by a feeling that he had neglected his duty.

The disturbances in the modern house in the Scottish town continued, but less often and with decreasing intensity. The boy was becoming aware of many other new interests in life and as these increased so the manifestations of the phenomena lessened.

The parents, after some weeks, felt it safe to bring their younger son home. And finally, after Christmas of that year, the boy, now twelve-years-old, was admitted to a small public school in England.

The phenomenon ceased.

Fears harboured by the parents that it would recur at school were soon allayed. There were no reports of anything untoward happening. With the arrival of his first holiday home fears again arose. Nothing happened. Finally the parents decided that it was over. Whatever 'it' had been, they never pretended to know or understand.

As for the boy himself, involved in new situations, the course of his life had changed so much that he not only never mentioned what had happened but seemed to have erased it from his memory. On the rare occasions that someone in the family alluded to it, he frowned and seemed genuinely puzzled as to where the conversation might be leading. Quickly discussion was diverted into other channels.

The Omega Factor

The Omega Factor