- Home

- Jack Gerson

The Omega Factor Page 2

The Omega Factor Read online

Page 2

Gradually the parents themselves began to forget at least the details of what had happened. If the subject came to mind they disagreed about the extent of disarray caused, each vying with the other to minimise what they had gone through.

One thing however neither the mother nor the father could forget. The psychiatrist had never returned. The boy's prediction had proved right. Driving to his consulting rooms some days after his visit, his Jaguar car had been in collision with an articulated lorry. The rear of the lorry, a long trailer carrying steel rods, had smashed into the side of the Jaguar.

The psychiatrist, strapped into the driving seat, had been impaled in the chest by one of the steel rods. He had died instantly, an expression of mild astonishment on his face.

TWO

In another place, at another time some years later, a middle-aged Professor of Philosophy at one of the smaller Oxford colleges became aware that he was under surveillance. Now it may be that any other Oxford professor might not have realised he was being followed and investigated but Andrew Scott-Erskine had worked for British Intelligence during the war, and for a time had lived in Paris while it was still occupied by the Germans. Thus he had cultivated an awareness which he had never lost, an ability to recognise that he was being followed.

Curiosity led him to question friends and students and he learned that discreet questions had been asked about his associations at Oxford, what societies he belonged to, were his lectures in any way Marxist-orientated, or indeed orientated towards any political extreme. Since he was unaware of any political affiliations that could be considered dubious (he was a member of the college Liberal Club, the OUDS and a small group of academicians who called themselves the Oxford Psychical Investigation Society) he was not unduly worried but he was rather curious. Why was he being investigated?

It wasn't as if he worked in a faculty which was relevant to problems of national security. Had he been a physicist of some note, or even worked in any experimental branch of applied or theoretical science, he could have understood it.

At first he resisted the temptation to face one of the followers, possibly out of an uncertainty as to whether he was actually being followed and not simply building up some paranoiac fantasy. But finally having identified over some weeks a thin dark young man in a trench coat and soft hat who seemed to dog his footsteps for certain periods each day he decided to face the young man on the kerb outside his rooms.

The young man stared at him in silence for some seconds, then gradually began to redden. 'You're making a mistake, sir.'

'I'm not making any mistake,' replied Scott-Erskine. 'I've had some experience of being followed during the war. By the Gestapo, incidentally, who were rather better at it than you.'

The young man stared down at his feet and shuffled them awkwardly. 'Look, I assure you...'

'Don't assure me,' Scott-Erskine went on. 'Save your assurances for the police.'

'I've done nothing illegal!' There was an edge of desperation in the young man's voice.

You've been following me for some time. If not you, someone else. Questions have been asked of my friends and colleagues... oh, they've told me about the questions. Now why am I being investigated? If you're some sort of credit agency I can assure you my meagre hire purchase commitments are scrupulously attended to and I have no immediate intention of taking on any more...'

Before he could finish the young man turned and walked away. Scott-Erskine took a step after him, realised that if he pursued the young man, he would look rather foolish and, almost certainly would have to fulfil his threat and call the police, and stopped.

He was aware for the next few days that he was being followed by a different man, this time identified as being tall, blond and slightly better at his job than the dark young man.

Then, quite suddenly after another week he realised he was no longer being watched. Thinking an even more expert shadow had taken over he became doubly alert. But he could not now identify anyone on his trail.

He then attempted to dismiss the whole affair as a case of mistaken identity. Yet inside him was a gnawing certainty that no mistake had been made.

Three weeks later he understood what had been happening. Returning from a morning lecture to his rooms he found three men waiting on his doorstep. One of them he knew.

Captain Kingsley had been, during the war, seconded from the Royal Navy to head the intelligence section to which the young Scott-Erskine had been assigned. He was considerably older now, his short hair grizzled, his face seamed with deep valleys. He was dressed in tweeds and carried a stick.

Scott-Erskine invited them into his rooms, produced a bottle of malt whisky and was introduced by Kingsley to his two companions.

'Mr Raglan is deputy Permanent Under Secretary at the Ministry of Defence and Commander Cole occupies my old position in Intelligence.'

As Scott-Erskine poured whiskies something clicked in his mind. 'You've been investigating me?'

Commander Cole replied. 'Gather you spotted my men. Of course they didn't know you'd been in Intelligence during the war. Sorry about it but we had to make sure you were still clean.'

'As a whistle,' Kingsley added. 'And you are. Of course I told them that. But they have to do their own investigation.'

'But why..?'

This time the man called Raglan replied. 'We want you back, Professor Scott-Erskine.'

A nervous shiver ran down Scott-Erskine's spine. He recognised the shiver; an anticipatory excitement before a mission in the old days. 'But, good God, you can't mean it! I'm too old for cloak and dagger games. And there must be plenty of people who can do the desk work.'

'This is something else,' Raglan cut in incisively. 'Something new. A new department.'

'But why me? I'm an academic. I haven't been near anything remotely connected with Intelligence...'

'It is because you are an academic. Kingsley recommended you.'

Captain Kingsley, whom Scott-Erskine later learned was semi-retired and now had the rank of Rear-Admiral, smiled encouragingly. 'Something up your street, old man.'

Raglan continued. 'And it is not strictly speaking Intelligence work of the nature you carried out during the war.'

Scott-Erskine remembered the war. In retrospect he had to admit he had enjoyed the war, his war; a never-ending battle of wits; a tension that had excited him; a knowledge that he was risking his life and that although the thought often terrified him it had also added something to his life. It had been at times like a drug, a dangerous stimulant that provided an edge to life that he had to admit he missed today.

Kingsley had always been a perceptive character. 'You don't exactly hate the idea, Andrew,' he said, his eyes twinkling.

'I'm prepared to listen,' he replied, realising that perhaps he had been for some time bored with his life at Oxford.

'Good!' said Raglan. You see we think you, with your knowledge of Intelligence work during the war, and with your academic training would be ideal to head Department Seven.'

'And what is Department Seven?'

'Nothing at present but an idea. We want you to create the department. The funds available will be generous, not to say lavish. You will of course come under the Ministry of Defence but within the actual department you will be in charge.'

'Same status as myself, old man,' Cole added.

'Arrangements can be made to release you from your college here,' Raglan was pacing the room now as if he had taken it over. 'And of course financially you will not lose by it...'

'But what is the function of the department?'

Raglan stopped and stared at him. His eyes were peculiarly piercing. 'First are you interested?'

'In principle, yes, but...'

'Fine. Then I will go on. You are I believe a member of a psychical research group?'

'Yes, but I don't see...'

Raglan cut in. 'You are aware that both the Americans and the Russians are unofficially carrying out experiments in extra-sensory perception, parapsyc

hology and a number of rather esoteric areas?'

'No, I wasn't,'

'It's true and we believe their results are quite interesting,' Cole said.

'Department Seven,' Raglan continued, ignoring Cole, 'is being set up to conduct such investigations. Only we are spreading our net wide. We believe that much unexplained phenomena may have a scientific basis which can be discovered and exploited. We believe that a team of trained people... trained in many disciplines, I may say... can uncover areas of experience of untold value to the defence of the realm and to the furtherance of knowledge.'

Raglan gave a cough and took a deep breath before continuing. 'We wish you to head this department. We believe you are ideally suited.'

A thought came to Scott-Erskine. 'If I said no...'

Cole broke in. 'We'd endeavour to persuade you. And we can be very persuasive.'

Scott-Erskine had some idea of how persuasive they could be. Men who did not fall into line found themselves unemployed or transferred, if they were in business, to some distant outpost. Some even -found themselves involved in criminal charges which they knew nothing about but of which evidence appeared from nowhere.

Again Raglan ignored both Scott-Erskine's expressed doubts and Cole's reply. 'My dear Scott-Erskine, we are giving you an opportunity to investigate some of the great and mysterious question marks in life today. I'm sure you would not refuse our offer.'

Make him an offer he can't refuse. The echo of a novel and film but in both the offer had come from gangsters. He smiled. When it came to governments, was there so much difference?

'It's interesting,' he said, aware of his understatement.

'I knew you'd find it so,' Raglan responded promptly. 'It's not often a man is given an opportunity to investigate the... the Omega factor.'

'The Omega factor?'

'Omega. The last letter of the great alphabet. The end. In this case the end of scientific knowledge. We are asking you to go further than that end. Beyond the end. To the Omega factor and further.'

The Omega factor. He liked the idea. He liked it a lot. And he knew now he would accept the offer. Not out of fear of their kind of persuasion, not even out of a desire to feel again the old excitement of the war. Because of the Omega factor. Because he wanted to go towards it and to go further.

Some time later, after many things had been discussed that thought was still with him.

The Omega factor.

Part One

ONE

Whiteness.

Not ordinary, everyday white. This was utter whiteness, a complete and positive void of colour. An absorption of the minimum of light rays and a reflection of the maximum.

That was always the first impression and it seemed to last for some time. Then gradually there came a greater definition. Vaguely against the whiteness came the awareness of the outline of the room. It was a square room yet the white was so intense that the size of the room was lost. The perspectives blurred.

He found then that he could look up and see the white light. It had a shape which he could only distinguish by the small globular area of great intensity.

Then came the consciousness that he was in the centre of the cube and he was sitting in a chair. It wasn't an ordinary chair; more like a dentist's chair in shape, a chair with arms, a high back and footrest. All were white. Barely a tinge of greyness that would denote a different texture.

He was then aware that he couldn't move, that he was strapped into the chair. White cord held his arms to the armrests and though he couldn't see his legs he knew they were similarly strapped to some undersection of the chair.

His mouth and nose were obscured by something, a kind of mask. This caused every breath he took to echo loudly in his ears, every exhalation and every inhalation.

He knew too that he was dressed in some kind of white gown. It was loose fitting but where it touched the skin it had a rough quality. Or so it seemed after a time. As if the longer he wore the gown the more aware he became of it brushing against his skin.

There were openings in parts of the gown and from these openings came wires stretching from tiny pads on his body and disappearing from his range of vision.

This worried him. At times he seemed to have a range of vision; and then at other times it seemed he was wearing spectacles and the lenses were white, opaque, obscuring completely his vision. And yet, even obscured by the lenses he could somehow still see the room. In his mind's eye, he wondered.

Time passed. He waited. As he waited it was as if he could feel his pores actually open and he was drenched in perspiration.

He knew he was afraid, terrified and he could do nothing. It was always the same and he knew it would get worse.

Soon the light in front of the chair would start flashing. It was easily visible through the opaque spectacles. He knew it was from a different source than the light above which always remained constant. For a time this new light source would flash rapidly, the effect being like a pulse beating, always at the same speed.

Gradually the pulsing of the light seemed to merge inside his head with another pulsating area that he had not been aware of before. It wasn't his heart-beat, the regular pulse of his body, but another deeper beat.

His hands started to tremble. This wasn't a manifestation of his fear but rather a reflex action caused by the light. At this point he made an effort of will to stop his hands from shaking. As he made the effort he knew it would be useless. It always was.

Then it was later. The throbbing light became much slower. The opaque lenses of the spectacles opened or slid to the side rather as if an optician was testing his eyes and sliding the glass away. He found himself staring again directly at the white glare; and then he felt he wanted to cry out for colour, for variation. He wanted even a grey shadow to break the vision.

His eyes seemed to clear and he was aware of the source of the light. There was a white box in front of him at eye level. He could dimly make out the lines of its shape and he almost wept at the minute variation.

The light was coming at a much slower rate but still at a regular interval. He found this increased his fear rather than lessened it.

Then, after a time, how long or how short he could never assess, the room blurred again. The blurred outlines started to revolve, or so it seemed. An impossibility? Yes, rooms were static. They didn't revolve. So the revolutions were inside his skull.

He shut his eyes. Still the light pulsed through his eyelids. He tried to grip the sides of the chair but his fingers only met air. He squirmed to try and release himself but he was still pinned to the chair.

At the same time although he knew he was pinned to the chair he also felt free of it- free not only of the chair but somehow free of his body.

He floated in a void of white light.

Nothing to threaten him, nothing but the whiteness.

Yet he was still afraid. The fear increased. There was nothing physical now, no increased pulse rate, no sensation of adrenaline pumping into the bloodstream.

Simple terror.

In the void there was a break in the whiteness. It became clearer. The shape of the break became less blurred. Form took over, shape became defined.

It was as if he was looking down at a grey structure, a distorted castle whose battlements led round and round, higher and higher until, at the highest point, by some strange distortion of perspective, they met the lowest point of the battlements and the eye moved again through the same progression.

'You're all right!'

The voice seemed to come from a vast distance, echoing through space.

'You're all right!'

He wasn't sure whether he was actually hearing it again or if it was the echo resounding in his head.

Tom Crane forced himself awake.

He was staring up into the face of his wife, Julia. He became fully aware that he was lying in bed, his body damp with perspiration and shivering.

He continued to stare up at Julia. Her face, heavy with sleep, was also

frowning. It was good to know she was concerned. It was always good to have that reassurance. Although at thirty-two years of age he shouldn't need reassurance.

He eased himself up onto one elbow.

'Oh, God, darling, I'm sorry.'

She smiled with obvious relief. 'For what? A nightmare?'

Crane forced himself to smile although he felt less like smiling than sighing with a sense of relief that he was awake and away from his fear.

'The nightmare!' he heard himself say.

The nightmare. God, he was a grown man, an adult and one with, in his own view, no great problems. So why should he have the nightmare? Why should he suddenly start having the same pointless dream and why should he be terrified by its very pointlessness.

He looked around the familiar bedroom. The walls were light blue, a calm soothing colour. No whiteness. Daylight, dimly filtering through the curtains, cast small pleasant shadows.

Julia, relaxed now, slid back to her side of the bed. The frown was still on her face but it seemed to Tom to have become one of mild annoyance.

'What time is it?' he said.

'Early,' she yawned a reply. 'Half-past six. Relax. Go back to sleep.'

'It's not worth it.'

They were both usually awake and up at seven o'clock every morning. Julia would leave for her job at Allied Computers and Crane, after a session with the morning papers, would either sit down at the typewriter or leave an hour later and head for Fleet Street and the large grey building wherein he would discuss interminably what he should be beating out on his typewriter.

'It's Sunday,' Julia said, nestling closer to him. 'All day.'

'Is it, by God?' he grinned, pleased. The one day they didn't have to get up. The one day he could spend entirely reading the papers. Then he remembered. Not this Sunday, at least not the entire day. He had to see someone somewhere around midday. The details came into his mind. The memory of the dream receded.

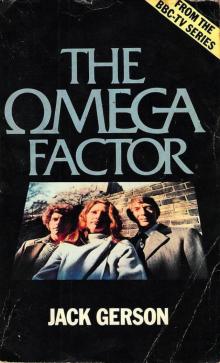

The Omega Factor

The Omega Factor